Investing Part 2: Eliminate Complexity, Mitigate Risk, Make Money

Risky. Overwhelming. Time-consuming. Impossible.

These are among the plethora of reasons that people claim they don’t invest. But it doesn’t have to be this way; investing can be easy.

There are plenty of effective ways to invest your money, time, and/or effort in a bid for large monetary returns: starting a business, buying rental properties, flipping houses, and even working your current job are just a few common examples. And while there’s nothing wrong with any of these approaches, they all share one common theme: they require a sacrifice of time and effort. If only there were a way to invest passively for those of us that don’t want to spend any time!

The Stock Market#

Enter the stock market, a massive online marketplace where you can invest in publicly-traded companies, funds, bonds, and other assets. The value of the assets in which you invest will be constantly changing depending on a myriad of factors. But if you invest in the right assets, the overall trend is up.

Each asset class available through the stock market has its own set of characteristics including risk, volatility (the size and speed of the changes in price), and expected return. Usually, assets with larger potential upside in regards to overall return are also riskier and more volatile, and vice versa. We want the best balance of the three: reasonably high return, manageable volatility, and low risk. The goal is for our money to grow steadily while not being so risky that it causes us to lose sleep (or worse, go broke).

Bonds, or loans to a government, corporation, or some other entity on which you collect interest payments, generally provide lower risk and volatility; these are desirable traits. But with minimal risk and volatility comes an almost negligible return, especially in today’s environment where those interest payments are historically small. While bonds do have a spot in a portfolio for many people, we need the majority of our investments to return more than the current capabilities of bonds, even if it means having to deal with an increase in volatility.

Investing in shares (small tradable pieces of ownership) of publicly-traded companies provides a higher expected return, but at a significant increase in risk and volatility. In many cases, buying shares of an individual company’s stock comes with far too much downside to make up for the potential upside. If you can imagine a spectrum of risk, then in general bonds would be toward one end and shares of individual companies would be on the other.

But what if you stick to investing in huge, well-known companies? How could that go wrong?

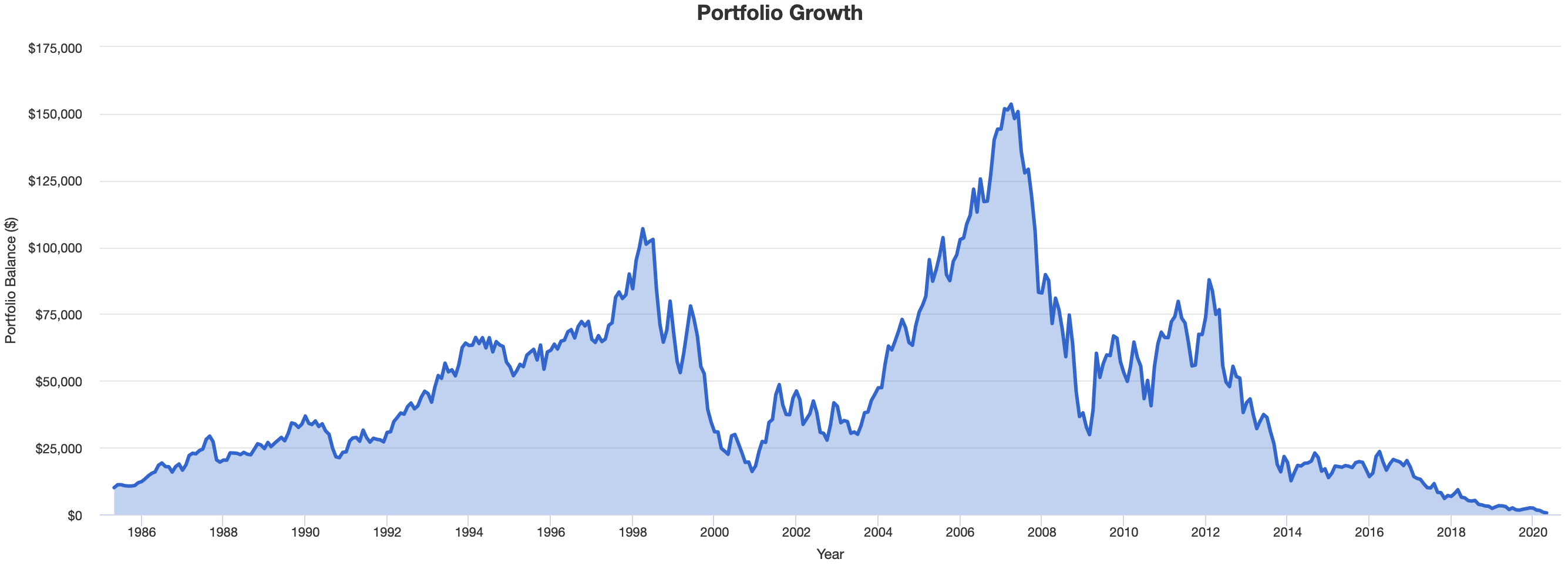

The graph below illustrates the fluctuating value over time of a $10,000 investment made in January, 1985 (as far back as the app will go) in a large company that you’d absolutely recognize if I included the name.

As you can see, this investment would have gone through a boatload of volatility, only for the initial $10,000 to end up shriveling down to about $531 as of the beginning of this month. That’s a compound annual loss rate of 8.04%, with the worst year dropping 77.68%! This can happen to any company, and it’s impossible to predict. That’s the risk.

Volatility and risk can be largely mitigated through diversification, or spreading your investments out over many different companies. But you still face the issue of “how do you choose the companies in which to invest?” Many professionals have years of experience and spend their entire careers researching this very question in order to make informed decisions while constantly changing their portfolio allocation to reflect their findings. Do you want to spend even a fraction of that time? I know I don’t.

Fortunately, we can invest in the stock market and get reasonably high returns with manageable volatility and practically no long-term risk, all while spending no time at all researching companies or changing the investments in our portfolios. This is all possible thanks to…

Index Funds#

Index funds are exactly what their names imply: funds that follow an index. An example of a broad market index is the S&P 500. The S&P 500 is a group of 500 of the largest publicly-traded companies in the United States.

The price of the index moves in a way that reflects how the prices of those 500 companies move; if the values of those companies go up, the index goes up, and vice versa. The S&P 500 is market cap weighted, which means that larger companies have a more significant impact on the movement of the overall index.

Index funds combine some of the best parts of bonds and individual stocks. You get steady growth over the long term that far exceeds the capabilities of bonds, and you get less volatility than individual stocks. And due to index funds inherently being diversified, the time commitment of researching and staying on top of the companies you invest in is nonexistent, since by investing in an index fund, you’re investing in numerous companies - 500 in this example.

The risk of losing your entire investment is also virtually eliminated by investing in a broad market index fund. Why? Look at it this way: if you invest in one company and that company goes bankrupt, you have nothing of value left. If you invest in an index fund like one that tracks the S&P 500 and a company in the index goes bankrupt, not only are you already diversified into 499 other companies, but another company will replace the failed one in the index, into which you automatically become invested. If all 500 companies in the S&P 500 go bankrupt at the same time, we have much, much larger problems than your or my investments becoming worthless.

In fact, it’s important to note that broad market index funds, like any other investments, fluctuate in value, and some years are bad years. But they always come back. If you find yourself in a down year, rather than panic selling (which is about the worst thing you can do), just think of it as buying the fund at a discount. When it comes back up, you’ll have even more shares that will appreciate in value.

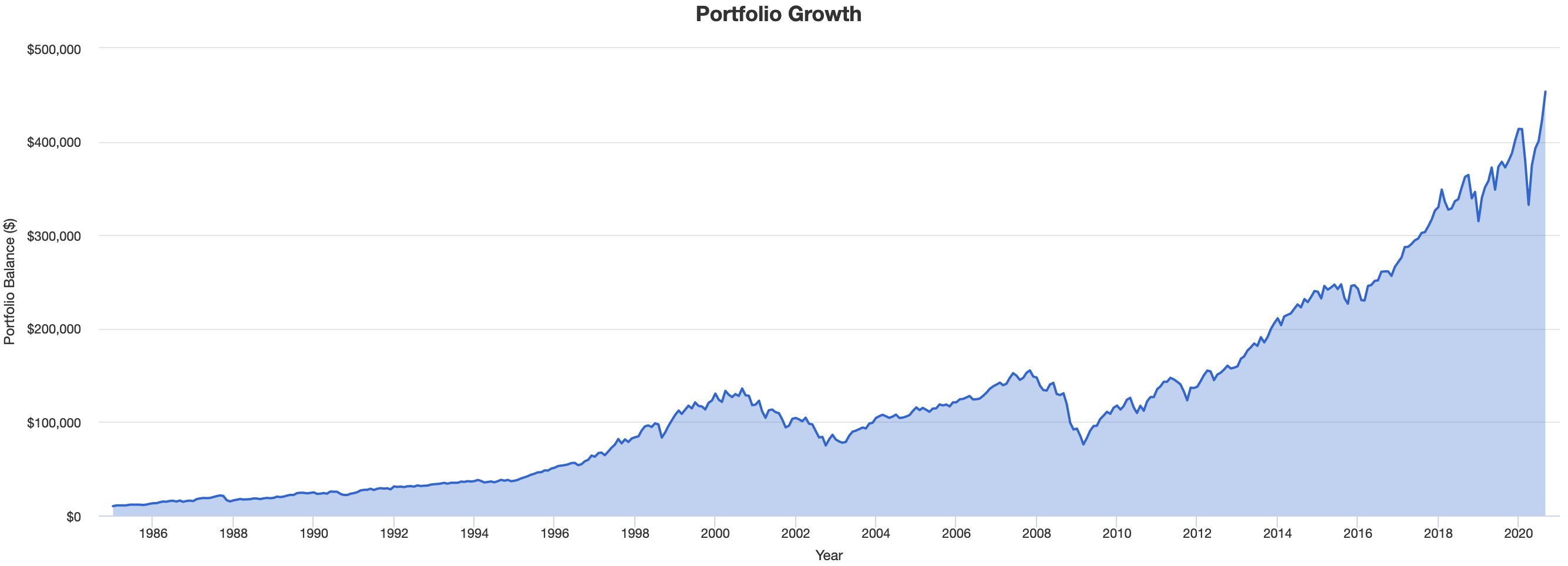

Let’s take a look at a graph of a $10,000 investment in an S&P 500 index fund in that same period of time as above, from 1985 to today.

The $10,000 investment in a cheap S&P 500 index fund with no additional contributions would have grown to $453,4881. That’s over 45x the initial investment amount, even through the dot com bubble burst of the early 2000s, the Great Recession almost a decade later, and COVID-19 in 2020. All for doing nothing!

This insane growth is due to an 11.29% compound annual growth rate (CAGR), meaning on average, the portfolio increased by 11.29% per year over that timeframe. The worst year was -37.02% and the best year was +37.45%. Now imagine how much more the value would have grown with a monthly contribution of really any amount.

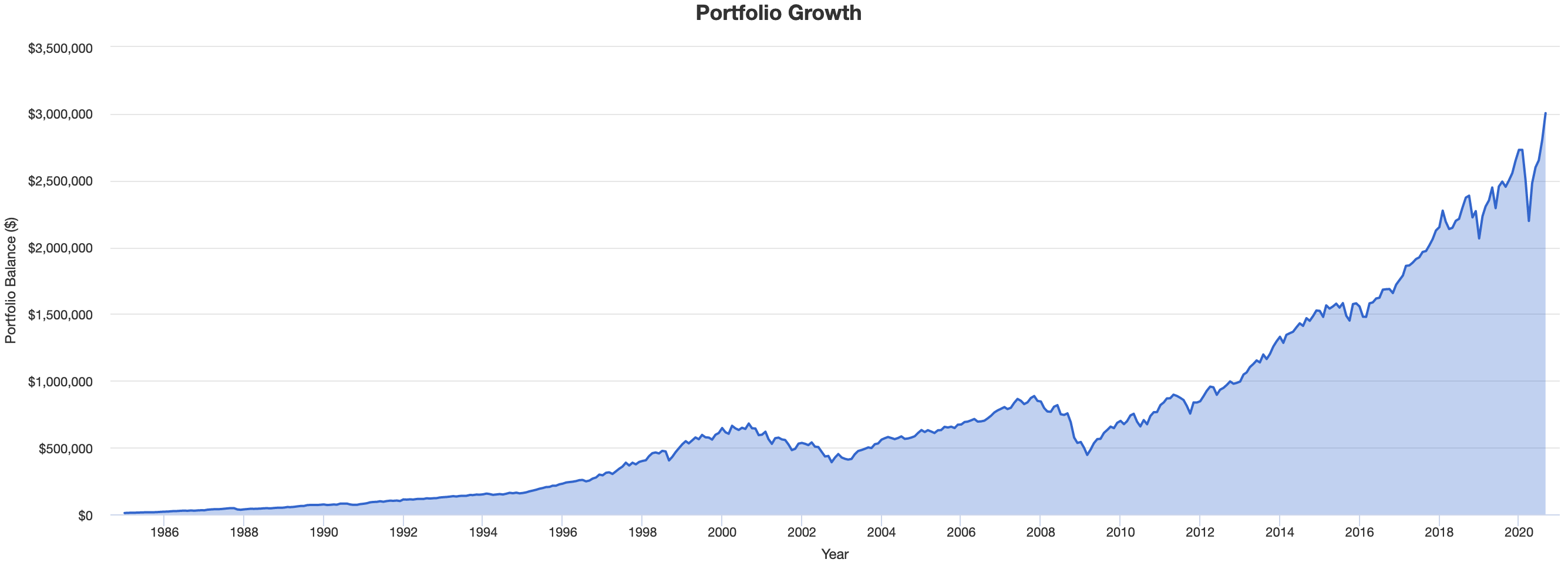

Luckily, you don’t have to imagine it. Here’s exactly what it would look like with contributions of $500 per month.

The graph looks pretty much the same, but the ending balance is a little higher. It’s $3,004,3712. This isn’t some fantasy simulation with made up returns; these are real numbers based on real data.

Surely all of these advantages must come at some cost to the investor! Well, brace yourself. The expense ratios, or fees associated with many of these funds, including the funds listed below, are 0.03%-0.04% per year (three or four one-hundredths of one percent), meaning 3 or 4 dollars per $10,000 you have invested per year. In the case of the funds below, those fees go to Vanguard; typically the fees go to the broker who owns the fund. Other brokers often have their own versions of these funds, some of which are free. Not a bad deal for almost guaranteed long-term returns.

Which Index Funds?

There are lots of index funds, some better than others. But anyone that invests in a broad market index fund, meaning one that tracks a very large portion of the economy, should do well over time. The most popular index funds among passive investors include S&P 500 Index Funds (explained above) and Total Market Index Funds. By purchasing a total market index fund, you are literally investing in every single publicly-traded company in the United States. S&P 500 funds and total market index funds are different, but their respective price movements are extremely correlated, so the decision between them makes almost no difference.

Popular examples of funds include but are not limited to:

| Ticker | Fund Name | Type |

|---|---|---|

| VTSAX | Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund Admiral Shares | Mutual Fund3 |

| VTI | Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF | ETF3 |

| VFIAX | Vanguard 500 Index Fund Admiral Shares | Mutual Fund3 |

| VOO | Vanguard S&P 500 ETF | ETF3 |

How does one invest in these or other funds? The easiest way to trade assets in the stock market is through an account with a broker, whether that’s a taxable brokerage account, an IRA (individual retirement account), or some other account. These are free to create at most brokers and can be done online in minutes. I’ll be writing a post soon outlining the differences between accounts.

Which Broker?

Which broker should you use to create an account and invest? This is mostly personal preference. You can invest in pretty much all the same funds and assets through any broker, although some brokers will charge lower or no expense ratios on their own funds.

The brokers most commonly mentioned in the FI community include, in no particular order: Vanguard, Fidelity, and Schwab, but there are plenty of others as well. I am not endorsing any specific brokers, nor am I attempting to dissuade anybody from any others, whether listed here or not.

The one recommendation I would make is to choose one that allows you to open multiple types of accounts, including taxable brokerage accounts and different types of IRAs. That way, as time goes on and your wealth grows, you aren’t forced to use multiple brokers to manage all of your accounts, unless you want to.

Conclusion#

Index funds are not a get-rich-quick scheme, but are instead an armor-plated vehicle on the practically guaranteed, slow and steady road to massive wealth and a comfortable, perhaps early retirement. Investing in broad market index funds eliminates essentially every risk and disadvantage of other tradable assets while requiring no time commitment on your part. Contribute early and consistently and you’ll be set for life.

So the next time someone warns you about the dangers of investing, think of how much longer a person would need to work in order to make up for that difference that they’re missing by not investing, and warn them that depending on a paycheck for their whole life is risky, overwhelming, time-consuming, and for many people, impossible.

(All charts in this post were generated using Portfolio Visualizer)

-

Adjusting for inflation, this is $184,299 in 1985 money. ↩︎

-

Adjusting for inflation, this is $1,220,987 in 1985 money. ↩︎

-

The differences between a mutual fund and an ETF are that mutual funds only update their prices (and therefore only process trades) at the end of the trading day, and they have minimum investment amounts in order to make your first purchase (often $3000). ETFs are like any other asset on the stock market in that there is no minimum, you buy them in shares, and their prices update in real-time. ↩︎